Blog Essay

Norupo (ᚾᚩᚱᚢᛈᚩ): The Norwegian Rune Poem in Heilung's Voice

What 'Norupo' adapts from the Norwegian Rune Poem, why it's a Younger Futhark alphabet chant, and how each rune name points to concrete, old ideas—cattle and wealth, hail and hardship, yew and endurance.

Norupo (ᚾᚩᚱᚢᛈᚩ) sets the Norwegian Rune Poem to music—a medieval mnemonic that walks through the sixteen characters of the Younger Futhark, the Viking-Age runic “alphabet.” The title Norupo (ᚾᚩᚱᚢᛈᚩ) isn’t a Norse word; it’s a runic NORU-PO—a straightforward shorthand for “Norwegian Rune Poem,” the medieval source Heilung explicitly cite for the lyrics. (Louder)

Where Heilung’s “Asja” leans into reconstructed ritual language, Norupo anchors itself in a real, transmitted text. The poem survives through early-modern copies (notably in Ole Worm’s 17th-century runological compilations) and catalogs a short image or proverb for each rune. That makes the track an “alphabet song,” but for runes: terse, concrete, almost proverbial lines meant to fix both name and meaning in memory.

Scholars classify this source as Younger Futhark, the 16-rune system of the Viking Age, widely attested on runestones and objects across Scandinavia. The poem likely served as a teaching aid, mapping each rune name to a vivid image—wealth sparking quarrels, hail striking crops, the river-mouth guiding journeys—so the sound and sense travel together.

What is a Germanic (Futhark) “rune”?

A rune is both a letter and a charged idea. The word goes back to Proto-Germanic rūnō “secret, whisper, counsel,” preserved in Old Norse rún, Gothic runa, and Old English rún—all meaning something hidden or confidential. From the start, then, runes were not just marks for everyday writing; they carried an aura of mystery, counsel, and spell-speech. That double life shows up in the sources: runes label ownership and trade goods, but they also name charms, oaths, and destinies.

As a script, runes are a Germanic adaptation of Mediterranean alphabets. The consensus is that early Germanic carvers borrowed letter shapes from the North Italic/Etruscan family (filtered through Roman contact), ultimately rooted in the Phoenician → Greek → Italic chain. The forms were reworked for carving on wood, bone, and stone—hence the angular strokes and straight lines that bite cleanly with a knife or chisel. The name futhark itself is a mnemonic built from the first six signs: f-u-þ-a-r-k.

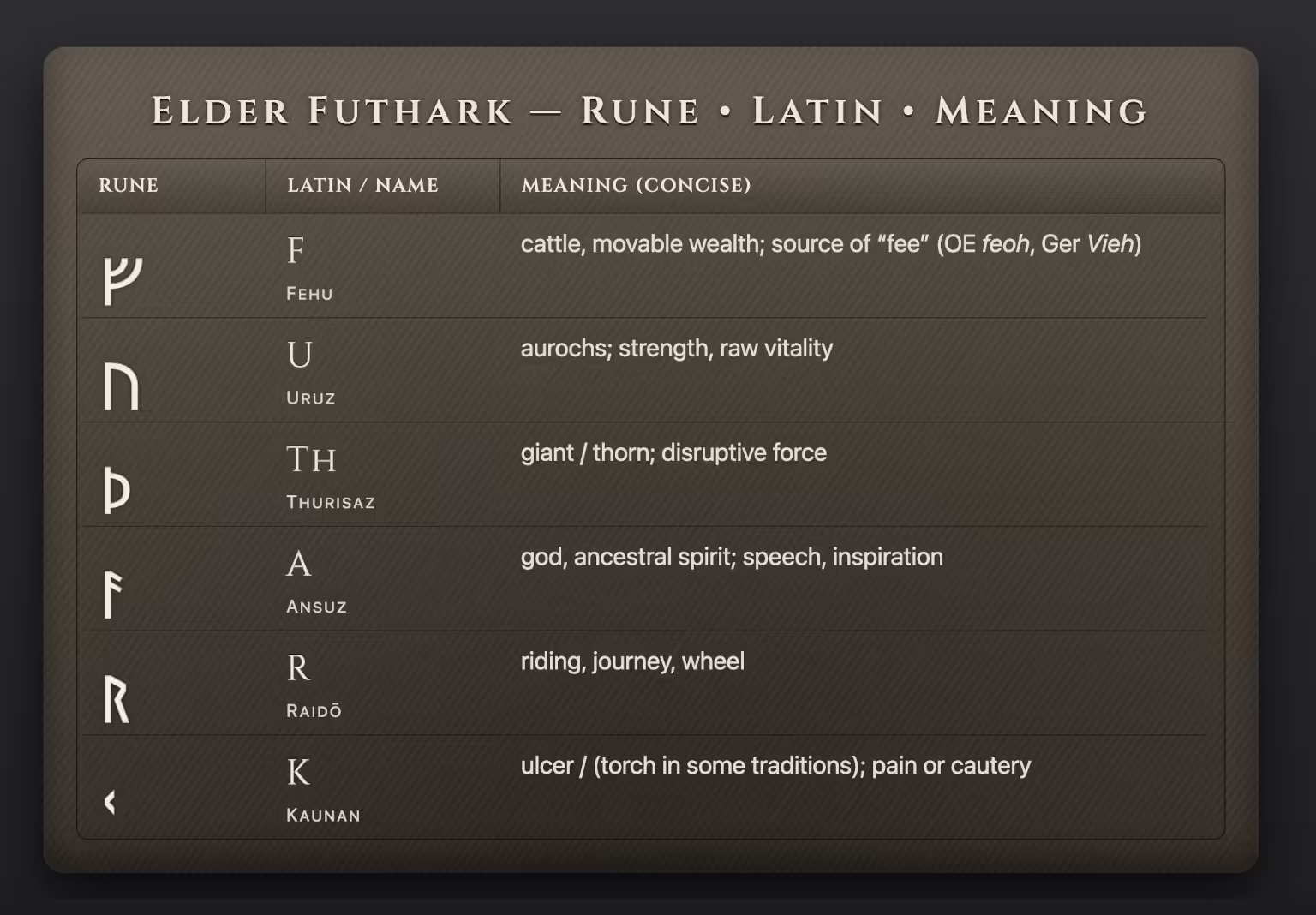

The earliest system, Elder Futhark (24 signs, c. 2nd—7th c. CE), appears across the Germanic world. In the Viking Age it collapsed to 16 signs as Younger Futhark, matching sound changes in Norse while streamlining the inventory. That’s the set the Norwegian Rune Poem teaches—each brief proverb ties a rune’s name to a vivid image so learners remember both sound and sense.

Runic inscriptions range from the practical to the numinous: names, maker’s marks, memorial stones, travel boasts, dedication formulas, and occasional “galdr”—sung or spoken magic. This breadth explains why rún could mean letter and mystery at once. In Norupo, Heilung leans into that older understanding: the alphabet is not only a tool for words, but a catalog of forces—cattle-wealth and hail, need and ice, sun and yew—each rune a compact of language, memory, and power.

The Rune Names: Meanings with Real Etymology

These lines aren’t abstract mysticism; they point to everyday realities and very old words. A few highlights with etymological color:

- Fé “wealth” is literally “cattle” in Proto-Germanic fehu. It’s cognate with Old English feoh/feo (money, property), which gives Modern English fee; compare German Vieh “cattle.” Livestock was movable wealth, hence the semantic slide from cows to cash.

- Úr in the Norwegian poem is “dross (slag) from bad iron,” whereas the Icelandic poem uses úr for “drizzle.” Same rune name, different local gloss—evidence the poems are mnemonic, not dictionaries.

- Þurs “giant, ogre” marks malign, disruptive power; the same root surfaces in dialectal English thurse and sits near Þór in the mythic lexicon.

- Óss in this poem means “estuary, river mouth” (navigation image), while Icelandic Óss means “god.” Same sound, different poem—again, mnemonics tuned to context.

- Nauðr “need, constraint” is the ancestor of English need, Old English nīed, and German Not “distress,” a word that still feels like a tightened belt.

- Hagall “hail” lines up with English hail (weather phenomenon), German Hagel—a farmer’s nightmare in one syllable.

- Ýr “yew” points to the evergreen used for bows; compare English yew and the wood’s reputation for toughness and sting (the poem even reminds you that it singes when it burns).

Compact reference (rune name → gloss → close cognates)

| Rune | Poem gloss (Norwegian) | Useful cognates / notes | URL-encoded (UTF-8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fé (ᚠ) | wealth, cattle-wealth, fee | OE feoh/feo → fee; German Vieh | %E1%9A%A0 |

| Úr (ᚢ) | dross/slag (from bad iron) | Alt. Icelandic poem: “drizzle” (úr) | %E1%9A%A2 |

| Þurs (ᚦ) | giant, harmful being | dialectal Eng. thurse; mythic Þursar | %E1%9A%A6 |

| Óss (ᚬ) | estuary, river mouth | homonym with “god” in Icelandic poem | %E1%9A%AC |

| Ræið (ᚱ) | riding | Eng. ride, road (semantic family) | %E1%9A%B1 |

| Kaun (ᚴ) | ulcer, boil | ON/Norse kaun “sore” (survives in modern Scand.) | %E1%9A%B4 |

| Hagall (ᚼ) | hail | Eng. hail; Ger. Hagel | %E1%9A%BC |

| Nauðr (ᚾ) | need, constraint | Eng. need; OE nīed/nēd; Ger. Not | %E1%9A%BE |

| Ís (ᛁ) | ice | Eng. ice; Ger. Eis | %E1%9B%81 |

| Ár (ᛅ) | good year/harvest, prosperity | ON ár “plenty”; near Eng. year (PGmc jērą) | %E1%9B%85 |

| Sól (ᛋ) | sun | ON sól; Eng. sun (different reflexes) | %E1%9B%8B |

| Týr (ᛏ) | the god Týr | Eng. Tuesday (< Tiw), PIE deiwos “sky god” | %E1%9B%8F |

| Bjarkan (ᛒ) | birch | Eng. birch; Ger. Birke | %E1%9B%92 |

| Maðr (ᛘ) | man, person | Eng. man; Ger. Mann | %E1%9B%98 |

| Lǫgr (ᛚ) | water, waterfall; also “law(s)” in other contexts | Eng. low (not a cognate); legal sense in ON lǫg | %E1%9B%9A |

| Ýr (ᛦ) | yew (bow-wood) | Eng. yew; archery associations | %E1%9B%A6 |

Note: These are Younger Futhark glyphs for the poem (e.g., ᚴ for Kaun, ᚼ for Hagall, ᛅ for Ár, ᚬ for Óss).

Lyrics and Translation

Below is a clean, copy-pastable pairing of the traditional text (as sung/adapted by Heilung) and a straightforward English rendering. Spelling reflects common editorial Old Norse/Old Norwegian conventions.

Norupo (ᚾᚩᚱᚢᛈᚩ) — paired lines (Old Norse / English), incl. male-voice interludes

Fé vældr frænda róge

(Wealth causes strife among kinsmen;)

Føðesk ulfr í skóge

(the wolf is reared in the forest.)

Úr er af illu jarne

(Slag comes from bad iron;)

Opt løypr ræinn á hjarne

(the reindeer often runs over the hard snow.)

Þurs vældr kvinna kvillu

(Giant causes women's sorrow;)

Kátr værðr fár af illu

(few are cheerful from misfortune.)

Óss er flæstra færða

(Estuary is the way of most journeys;)

Fǫr; en skalpr er sværða

(but a scabbard is the way of swords.)

Ræið kveða rossom væsta

(Riding, they say, is worst for horses;)

Reginn sló sværðet bæzta

(Reginn forged the finest sword.)

Kaun er barna bǫlvan

(Ulcer is children's affliction;)

Bǫl gørver nán fǫlvan

(evil makes a corpse pale.)

Hagall er kaldastr korna

(Hail is the coldest of grains;)

Kristr skóp hæimenn forna

(the Ruler shaped the ancient world.)

Nauðr gerer næppa koste

(Need leaves scant choices;)

Nøktan kælr í froste

(the naked one grows cold in frost.)

Uunia, Runo, Sigurd

(Male chant—phonetic/ritual syllables; evokes "runes / victory / Sigurd.")

Fähig ani, Regina, Gunada

(Male chant—phonetic/ritual syllables; not a direct lexical line.)

Ís kǫllum brú bræiða

(Ice we call a broad bridge;)

Blindan þarf at læiða

(the blind must be led.)

Ár er gumna góðe

(A good year is good for men;)

Get ek at ǫrr var Fróðe

(I say that Fróði was generous.)

Sól er landa ljóme

(Sun is the light of the lands;)

Lúti ek helgum dóme

(I bow to holy judgment.)

Týr er æinendr ása

(Týr is one-handed among the gods;)

Opt værðr smiðr blása

(often the smith must blow the bellows.)

Uunia, Runo, Sigurd

(Male chant—phonetic/ritual syllables; ritual refrain likely voiced by Kai Uwe Faust.)

Fähig ani, Regina, Gunada

(Male chant—phonetic/ritual syllables; no straightforward gloss.)

Bjarkan er laufgrønstr líma

(Birch is the greenest limb with leaves;)

Loki bar flærða tíma

(Loki brought times of deceit.)

Maðr er moldar auki

(Man is the increase of earth;)

Mikil er græip á hauki

(mighty is the hawk's claw.)

Lǫgr er, fællr ór fjalle

(Water is what falls from the mountain—)

Foss; en gull ero nosser

(a waterfall; and jewels are of gold.)

Ýr er vetrgrønstr viða

(Yew is the greenest of trees in winter;)

Vænt er, er brennr, at sviða

(fair it is, when it burns, that it singes.)Notes on variants: some lines differ across manuscript traditions—e.g., the “world-shaper” line appears as “Kristr skóp…” in Christianized copies and as a theistic epithet (Herjan, “army-father,” i.e., Odin) in others. Norupo performances tend to standardize spelling for musical flow.

The interludes, or short refrains, are delivered by the male voice (likely Kai Uwe Faust) and function as ritualized, phonetic calls rather than strict Old Norse vocabulary; they reinforce the chant’s cadence and thematic cues (“runes,” “victory,” heroic names) rather than adding literal narrative lines.

What the Runes Are Doing in These Lines

The poem’s design is mnemonic minimalism. Each rune name cues a semantic field:

- Fé doesn’t just mean “money.” It points to movable wealth, the kind that breeds, wanders, and creates jealousy. The line warns that property strains kinship—the oldest social problem in one couplet.

- Nauðr is what it sounds like: need, duress, the vise that narrows options. The next clause—“the naked grows cold”—grounds it in the body.

- Hagall is meteorology turned moral: a sudden, grain-killing event you can’t bargain with.

- Óss as “river mouth” imagines wayfinding: ships entering and leaving, travels beginning and ending. In other poems, the same sound means “god.” Here the estuary image served students of navigation more than theology.

- Ýr closes the set with yew, a bow-wood and a winter-green tree. Durable, slightly dangerous, perfect for a final note about heat and singe.

Across the stanza-set, you can feel the curriculum: husbandry and property, metallurgy, weather, seamanship, craft, law, the seasons, and the gods—everything a young person in a maritime, agrarian society should remember.

Putting It All Together

Norupo is pedagogy turned into chant. Heilung keep the poem’s plain speech and wrap it in pulse, drone, and call-and-response, so each concrete image—cattle, hail, estuary, yew—lands in the body before it lands in analysis. Where alphabet songs usually end when the letters do, this one leaves the taste of ethics: wealth strains kin first; need narrows choice; weather humbles hope; craftsmanship and right worship steady the hand.

Conclusion

Norupo doesn’t just recite an alphabet; it reopens a doorway. The Norwegian Rune Poem was once a memory path for apprentices—short, hard images you could carry on a ship or into winter. Heilung sets that path ringing again, turning each rune into breath and heartbeat: cattle become wealth that strains kinship, hail becomes the sudden will of the sky, need tightens like a belt, the yew holds its green fire through snow. Between verses, the male voice cuts in like a ritual call across the longhouse, reminding you this isn’t lecture—it’s working song.

What the poem names, the band embodies. Drums make the river-mouth move; drones hold the ice steady; voices lift Týr’s steadiness and the sun’s return. By the end, the runes feel less like letters and more like presences—things you can stand beside: law and water, journey and craft, concealment and counsel. Norupo brings the old mnemonic back to life as ceremony, letting the poem’s plain words and Heilung’s trance bind together into a single, shared rite.

Sources & Further Reading

- Overview of the rune-poem tradition and the Norwegian set; context for Younger Futhark’s 16 runes. (Wikipedia)

- Skaldic database entry and source/manuscript notes; early-modern transmission (incl. Ole Worm). (skaldic.org)

- Representative English translations of the Norwegian Rune Poem. (ragweedforge.com)

- Heilung’s usage and fan-documented lyric/translation pairings. (Lyrics Translate)

- Background on the Younger Futhark as the Viking-Age rune set. (lufolk.com)

If you want, I can also generate a compact side-by-side PDF of the rune names, lines, and cognates for printing or MP3 tagging.