Blog Essay

The Lost History of Arianism: When 'Christian Europe' Wasn't Nicene Yet

Arianism didn't just lose a debate for a while–large chunks of post-Roman Western Europe were ruled by Arian (often Homoian) Christian elites. This article explains what Arianism actually taught, how it spread through the Goths and other Germanic kingdoms, why Nicene/Chalcedonian Christianity outlasted it, and how politics, demography, and institutions turned creed language into 'orthodoxy.'

Arianism is one of those chapters that makes the tidy “Rome persecuted Christians → Constantine converts → Europe becomes Christian” story fall apart. Not because Christianity didn’t grow or consolidate, but because which Christianity mattered—and for a while, much of the post-Roman West was ruled by Christian elites whom later “orthodoxy” labeled heretical. The irony is that this wasn’t fringe. It was royal, episcopal, and institutional in multiple kingdoms. The reason you rarely hear the full story is simple: the winners wrote the catechisms, and the map eventually got recolored.

At the core, Arianism (and the broader family of “non-Nicene” positions it gets lumped into) was a fight over what Christians mean when they call Jesus “God.” The Council of Nicaea (325) drew a hard boundary by using homoousios (“of one substance”) to affirm that the Son shares the same divine essence as the Father, and it condemned Arianism as heresy. (Encyclopedia Britannica) But the controversy didn’t end in 325; it churned for decades. By 381, the First Council of Constantinople reaffirmed and expanded the Nicene framework and condemned Arianism again, tightening what would become the mainstream “Nicene” definition of Christian orthodoxy. (Wikipedia)

Meanwhile, the West was about to become politically unstable, and that’s where the “lost history” starts to matter. As Roman authority fragmented, new Germanic-led kingdoms formed across the former Western Empire—Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Burgundians, Suebi, later Lombards. Many of these elites were already Christian, but their Christianity often came through frontier missionary networks associated with Homoian theology (frequently and misleadingly flattened into “Arianism”). Modern scholarship is blunt about this: calling the Goths simply “Arians” can be inaccurate, because their theology wasn’t necessarily Arius’s exact program—“Arian” becomes a polemical umbrella for multiple anti-Nicene positions. (MDPI)

Arianism Differences

Here’s the doctrinal spine of the dispute. This table is intentionally practical: it compares the Nicene position to the common “Arian-ish” claims, and then to the Homoian style that shows up so often in the Germanic kingdoms.

| Topic | Nicene (imperial mainstream after 381) | “Arian” (Arius / classic anti-Nicene thrust) | Homoian (common among Goths/kingdom elites) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is the Son eternal like the Father? | Yes: no “when he was not” | No: the Son has an origin; not co-eternal | Often avoids the philosophical framing; tends toward non-Nicene subordination |

| Essence language (what “God” is) | Son is homoousios with Father (“same substance”) (Encyclopedia Britannica) | Rejects homoousios; Son is not the same essence as Father | Typically avoids essence terms and prefers “like the Father according to Scripture” (a strategic compromise) (UBC Open Library) |

| Status of the Son | Fully divine, equal in being | Highest created/divine agent but not fully God in the Nicene sense | Subordinationist tendency without committing to Arius’s sharper metaphysics (Oxford Research Encyclopedia) |

| Why it mattered politically | Became the empire’s “standard” and later state-backed orthodoxy | Became legally and socially vulnerable after imperial alignment | Became a marker of elite identity in some western kingdoms—until those kingdoms flipped or fell |

Two clarifications keep you from getting lost. First, “Catholic/Chalcedonian” is not the right opposite of “Arian” in the early period; the opposite is “Nicene.” Chalcedon (451) is a later council about how Christ’s divinity and humanity relate (“two natures… without confusion/change/division/separation”). (Wikipedia) You can be Nicene and still fight bitterly over Chalcedon (as the later non-Chalcedonian controversies prove). Second, the Great Schism is not “Arians vs Catholics”; it’s a much later Rome—Constantinople rupture inside Nicene/Chalcedonian Christianity. (Wikipedia)

Early Christian History

For the first few centuries, Christianity grew largely without state force—not because it was always gentle, but because it lacked coercive machinery. The major political pivot under Constantine is often retold as “he made Christianity the state religion,” but that’s wrong. The Edict of Milan (313) legalized Christianity and granted toleration; it did not make Christianity the official religion. (Wikipedia) Official “this is the normative imperial faith” comes later with the Edict of Thessalonica (380), which made Nicene Christianity the state church and explicitly condemned other creeds such as Arianism. (Wikipedia)

That matters because it explains the later Germanic situation. When Germanic peoples interacted with the empire on the frontier—serving as foederati, trading, settling, fighting—they were exposed to Christianity through real human channels: bishops, captives, mixed communities, and missionaries. Ulfilas/Wulfila, a 4th-century Gothic bishop, is the iconic case: he evangelized Goths and is credited with overseeing a Gothic Bible translation tradition. (Wikipedia) He operated in the era when the Arian controversy was still alive, and later observers routinely described Gothic Christianity as “Arian,” even though the details likely reflect broader Homoian networks rather than Arius himself. (MDPI)

So you get a weird snapshot around the year 500: the Roman Empire (especially the East) is officially Nicene; the post-Roman West is full of kingdoms where many ruling elites are Homoian/Arian-leaning Christians, while many local Roman populations are Nicene. That’s not a clean “pagan → Christian” line. It’s a messy “Christian vs Christian” map.

Who Believed in Arianism

At a high level, “Arian” on the map usually means the ruling elite’s church alignment, not the private spirituality of every farmer in the kingdom. It also often means Homoian rather than “Arius, strictly.” With that in mind, here are the big adopters and why they mattered:

- Goths (Visigoths and Ostrogoths): evangelized through frontier missionary networks in the 4th century; commonly labeled “Arian” in later sources, but often better understood as Homoian-leaning. Ulfilas is the key early figure tied to this channel. (Wikipedia)

- Vandals: established a powerful kingdom in North Africa; their elite alignment is classically described as Arian, and later imperial reconquest erased the kingdom—one major way “Arian Europe” shrank was simply that some Arian kingdoms stopped existing. (Wikipedia)

- Burgundians and Suebi: both show up in the “Arian kingdoms” story, often with mixed or shifting alignment over time; the key pattern is that these were post-Roman elites navigating legitimacy with Nicene bishops and Roman populations. (The details vary by place and decade, which is why simplified textbooks dodge it.) (Wikipedia)

- Lombards (later): commonly described as arriving with Arian leanings and drifting toward Nicene alignment over time as integration deepened. (Wikipedia)

The Politics That Made “Orthodoxy” Win

If you want it blunt: Nicene/Chalcedonian Christianity didn’t “win” because a neutral jury declared it logically superior; it won because it became the creed of the most durable institutions. Nicaea (325) drew the doctrinal boundary and Constantinople (381) reinforced it; then the empire backed it; then the post-Roman West increasingly found that legitimacy, administration, and social cohesion ran through Nicene bishops. (Encyclopedia Britannica) Once the incentives line up like that, theology becomes a career and statecraft question as well as a metaphysical one.

You can see this dynamic with almost embarrassing clarity in Visigothic Spain. Under Reccared I, the kingdom flips from Arianism to Catholic (Nicene) Christianity, and the Third Council of Toledo (589) formalizes the change. The council’s own summary highlights two crucial realities: it marks the Visigoths’ entry into the Catholic Church, and it includes the transfer of Arian bishops and clerics into Catholic dioceses—meaning assimilation, not just suppression. (Wikipedia) In other words, yes: some Arian clergy appear to have abjured Arianism and continued their ecclesiastical careers under the winning regime, because the alternative was marginalization once the king and the kingdom’s power structure moved. (Wikipedia)

This “flip and absorb” pattern sits alongside a harsher pattern: conquest and eradication of Arian political structures. When kingdoms like the Vandals and Ostrogoths were destroyed or absorbed, their institutional churches didn’t get to negotiate from strength. Arianism didn’t just lose arguments; it lost courts, treasuries, armies, and continuity.

What Arianism Looked Like on the Ground

One of the most misunderstood parts is the social texture. In many of these kingdoms, “Arian vs Nicene” was not a constant civil war; it was often a form of religious dualism by class and ethnicity. The ruling group had its bishops and liturgy; the Roman population had theirs. Sometimes this coexisted; sometimes it turned into conflict; sometimes it became a lever for rebellion or diplomacy. The important point is that it was politically legible: your bishop network was a power network, and your creed affiliation could signal whether you were aligned with the old Roman order or the new ruling elite.

This is also why calling Arianism “swept under the rug” isn’t crazy. If you’re catechizing later Christians, you don’t want to emphasize that (a) bishops and kings can be wrong for centuries, and (b) Europe’s “Christianization” included long periods of Christians calling other Christians illegitimate. It complicates the story people want to tell about unity, continuity, and inevitability.

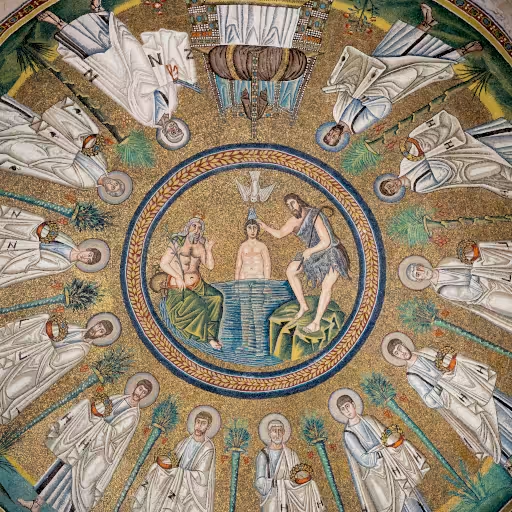

Arian Art, Reuse, and Damnatio Memoriae

Arian churches and images weren’t always smashed; more often they were converted, edited, or overwritten. Ravenna is the poster child: the Arian Baptistery keeps its baptism dome because the imagery is broadly compatible with Nicene use after reconsecration, while Sant’Apollinare Nuovo shows deliberate political-theological editing where Theodoric’s Arian court imagery was removed and replaced, leaving visible remnants (hands on columns) as evidence of regime change.

Was Arianism’s Downfall a “Populist Movement”?

Not in the modern “the masses rose up and overthrew the elites” sense. It was more like demographic and institutional gravity:

- The Arian/Homoian elite was often a minority ruling layer.

- The local Nicene bishops were embedded in urban administration, literacy, and legitimacy.

- When a king flipped (e.g., Spain’s conversion culminating at Toledo 589) or when a kingdom fell to conquest, the Arian church structure either got absorbed or collapsed.

Elites vs “vulgar” populace: yes, that’s broadly the pattern

In many post-Roman western kingdoms, “Arian” (often Homoian) Christianity was disproportionately the religion of the ruling Germanic elite, while much of the local Latin-speaking population and their bishop networks were already Nicene (especially in cities). Theodoric in Ravenna is explicitly described as commissioning separate places of worship rather than uprooting the existing Nicene community—another tell that these could be parallel systems.

So the populace mattered mainly because they were already Nicene in many regions, making Arianism hard to sustain long-term once elite sponsorship wobbled. That’s “populist” only in the very loose sense that demography + existing local institutions favored Nicene survival—but the big switches were usually elite/political decisions, not street revolutions.

Conclusion

Arianism is “lost history” mainly because it doesn’t fit the propaganda arc. It shows that early Christian doctrine was not just a spiritual development; it was also an institutional contest, and for a meaningful stretch the post-Roman West ran on a kind of Christian pluralism where the elites and the masses often belonged to different churches. Nicene Christianity’s eventual dominance was real—and it became “orthodoxy” in part because it ended up welded to the strongest surviving political and ecclesiastical machines, then reinforced through councils, law, patronage, and demographic absorption. Nicaea set the boundary, Constantinople reinforced it, Thessalonica armed it with the state, and Toledo shows how a “heretical” ruling class can be brought into line by flipping the top and absorbing the clerical infrastructure. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

If you want a more honest mental model of Christian history, this is it: “creeds” are theology, but they’re also statecraft. Arianism didn’t just lose a debate. It lost the ability to reproduce itself as a durable institution once the kings, councils, and courts that sustained it either converted or disappeared.

Sources

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — First Council of Nicaea (325): homoousios, condemnation of Arianism. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- First Council of Constantinople (381): reaffirming/expanding Nicene creed, condemning Arianism. (Wikipedia)

- Edict of Milan (313): legalization/toleration, not state religion. (Wikipedia)

- Edict of Thessalonica (380): Nicene Christianity as state church; condemnation of other creeds. (Wikipedia)

- Ulfilas/Wulfila and Gothic mission context; “Gothic Arianism” nuance. (Wikipedia)

- Oxford Classical Dictionary entry summary: “Arianism” as a polemical umbrella for subordinating positions. (Oxford Research Encyclopedia)

- Third Council of Toledo (589) and Reccared’s conversion; transfer/absorption of Arian clergy. (Wikipedia)

- Chalcedonian Definition (451): two natures formula; distinction from Arian controversy. (Wikipedia)

- East—West Schism overview (for “this is not that” clarity). (Wikipedia)